Introduction

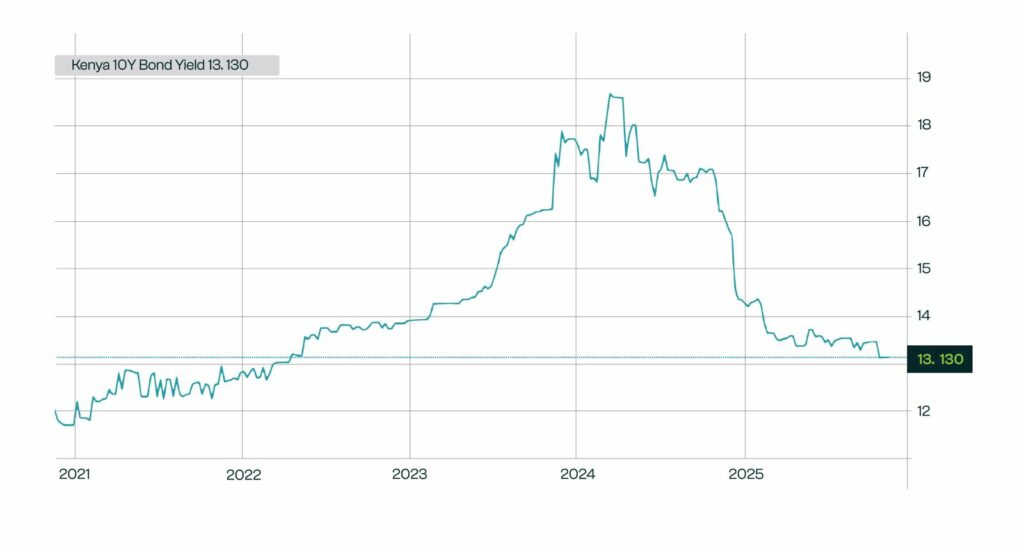

Kenya’s re-entry into the Eurobond market in 2024–2025 is one of the most significant financial shifts in Africa’s recent economic narrative. In late 2023, the country was nearing distress, with its 2024 Eurobond trading above 18% (Bloomberg, 2023), signalling deep investor doubt about Nairobi’s ability to refinance the 2-billion-dollar maturity ahead. Yet by February 2024, Kenya issued a 1.4-billion-dollar Eurobond at a coupon of 9.75% drawing 6 billion dollars in investor orders (Reuters, 2024). A year later, in 2025, a second 1.5 billion dollar dual-tranche issuance drew an even larger 7.3-billion-dollar order book (Bloomberg, 2025).

Kenya 10-Year Government Bond Yield – Quote – Chart – Historical Data – News

Such a dramatic reversal did not happen by accident. It emerged from a multi-year journey of fiscal tightening, debt-restructuring strategy, IMF-backed discipline, and a broader global re-opening to frontier-market debt after two years of hawkish US monetary policy. Understanding Kenya’s comeback requires looking at how it lost market access, what changed in its fiscal trajectory between 2020 and 2025, how markets responded, and what this means for the country’s economy, trade, businesses, and investors going forward.

Kenya’s Fiscal Story: Fall, Repair, and Market Re-entry

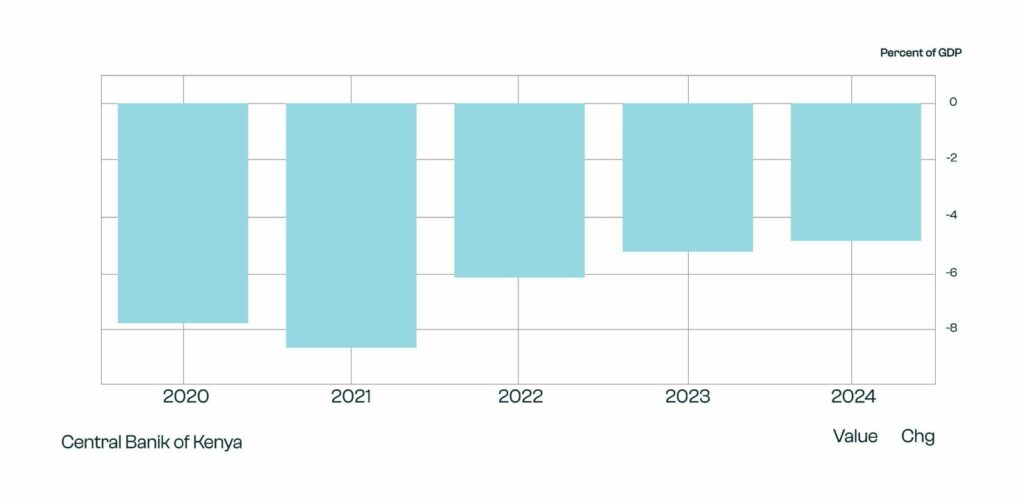

Kenya’s challenges began well before the 2024 maturity surfaced. Throughout the early 2020s, external borrowing expanded faster than export earnings. Public debt rose into the mid-60 percent range relative to GDP, reaching 68% in 2023 (IMF, 2024). At the same time, debt service consumed an increasingly large share of revenue, and fiscal deficits remained elevated at 5.8% in 2023 (National Treasury, 2024). When the US Federal Reserve tightened aggressively in 2022–2023, yields on African Eurobonds climbed sharply. Kenya’s bonds sold off so heavily that the 2024 maturity became almost untradeable except at distressed yields.

Yet the numbers began shifting sharply from 2023 onward. Kenya undertook a significant fiscal correction under its IMF program, reducing the deficit from 5.8% of GDP (2023) to 4.3% (2024), with a target of 4.0% in 2025, its tightest stance since before the pandemic. Public debt, which had steadily risen, stopped climbing and began easing from 68% in 2023 to 66.1% in 2024, and is projected at 64.8% in early 2025 (IMF, 2025).

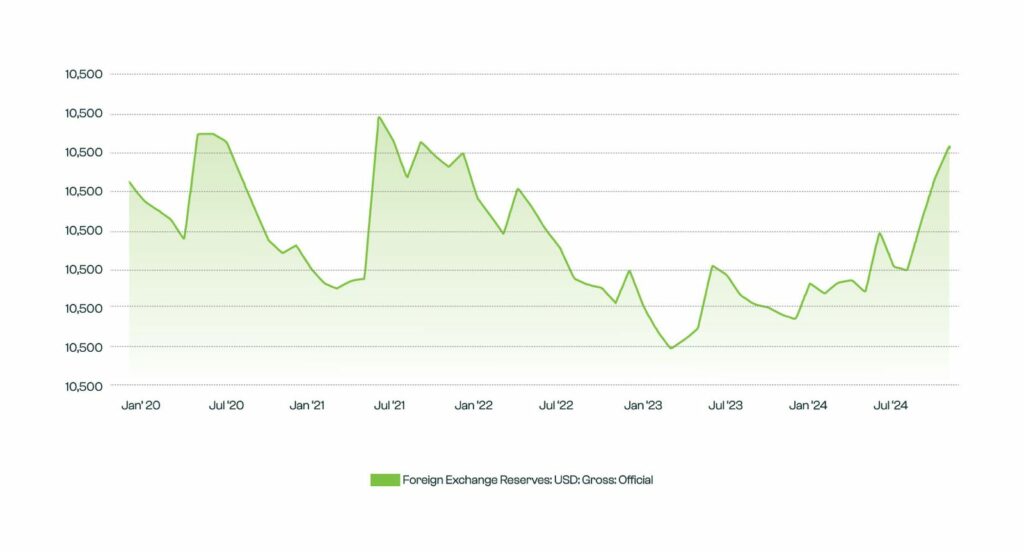

Foreign exchange reserves, which had fallen to 7.1 billion dollars in 2023, began strengthening to 7.7 billion in 2024, then 8.5 billion dollars by February 2025 (CBK, 2025), the highest since 2021. The current account deficit narrowed as well, from –5.0% in 2023 to –4.1% in 2024, with a projection of –3.8% in 2025 (IMF, 2025). These improvements helped restore confidence that Kenya could manage its external position without a disorderly restructuring.

Kenya Foreign Exchange Reserves, 2000 – 2025 | CEIC Data

The most decisive shift, however, came from Kenya’s early repayment strategy. Instead of waiting for the June 2024 Eurobond to trigger a liquidity crisis, the government refinanced and repurchased more than 1.5 billion dollars of the note ahead of deadline using a mix of concessional debt, syndicated loans, and the February 2024 Eurobond (National Treasury, 2025). That bold pre-payment signalled both capacity and commitment to honour obligations and it changed the market narrative almost instantly.

The impact became visible in secondary market performance. Kenya’s Eurobond yields fell from 18.2% (Nov 2023) to 11.3% (Dec 2024), and then to 8.9% (Mar 2025) (Bloomberg, 2025). This data point, more than any policy statement, captured the shift in investor perception from near-default to credible high-yield borrower.

Ratings agencies reacted accordingly. Moody’s maintained Kenya at Caa1 stable in early 2025, Fitch upgraded the outlook to stable with a B-, and analysts such as Standard Bank described Kenya’s issuance as the “reopening of the sub-Saharan sovereign pipeline,” suggesting that Ghana, Ethiopia, and Côte d’Ivoire could follow a similar model of reform-led re-entry.

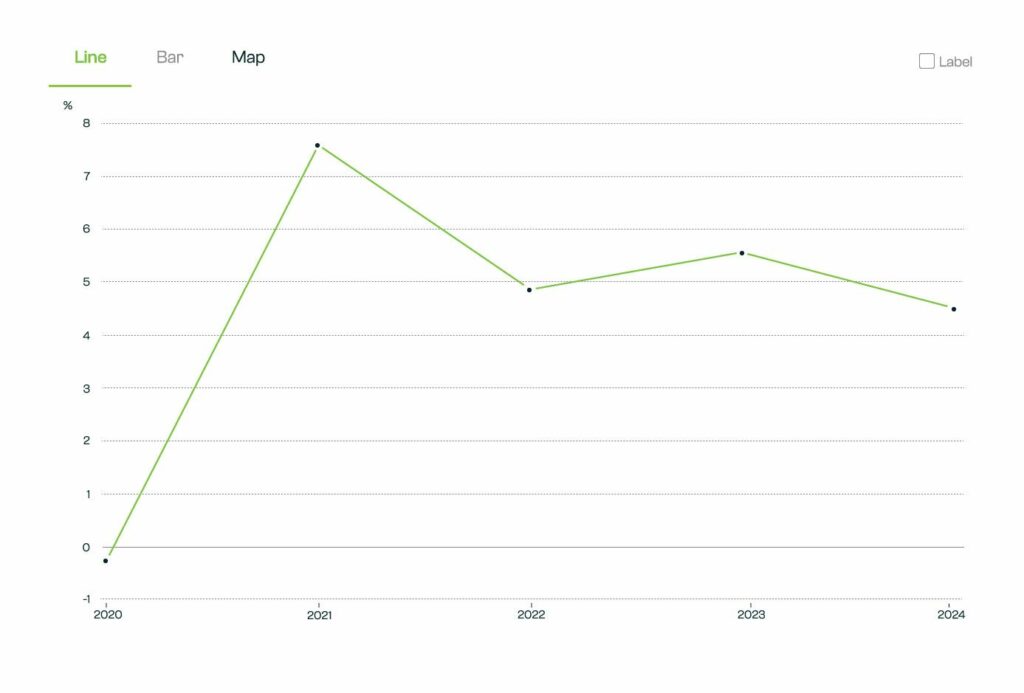

Still, the domestic effects of Kenya’s fiscal adjustment have been more nuanced. GDP growth slowed from 5.7% (2023) to 4.7% (2024), with the World Bank projecting 4.5% for 2025, largely due to tight monetary policy, reduced government spending, and declining private-sector credit. Businesses have faced high interest rates, elevated non-performing loans, and constrained access to capital. While the macro indicators improved, households felt the pressure of new tax measures and subsidy rationalisation required under the IMF program.

GDP growth (annual %) – Kenya | Data

This creates an interesting tension: externally, Kenya looks stronger and more credible; internally, growth is weaker and the cost of stability is visible. Yet this tension does not nullify the benefits of stabilisation, it simply highlights that the next phase must shift from stabilisation to expansion.

Strategic Takeaways

Government

Kenya’s comeback reduces short-term refinancing pressure and gives the government breathing room after years of elevated rollover risk. Higher FX reserves strengthen external buffers and support a more predictable fiscal environment. But external borrowing still carries high coupons, meaning discipline cannot weaken. The Treasury must maintain credible fiscal consolidation even in politically sensitive periods. Any reversal in tax administration, spending controls, or debt strategy could quickly undermine the confidence regained. Kenya has earned investor trust, but sustaining it will require consistent, transparent governance.

Economy

Macroeconomic stability has returned, with a firmer shilling and better-controlled inflation improving predictability across the economy. However, tight monetary conditions still restrict private credit and suppress domestic demand. Growth has slowed from 5.7% to around 4.5%, reflecting the weight of elevated interest rates. Households and firms feel the impact of tax adjustments and reduced government spending tied to the IMF program. Kenya is now in a stabilisation phase rather than an expansion phase. The fundamental challenge is to convert stability into stronger, broad-based economic growth.

Trade

Trade benefits significantly from stronger reserves and a more stable currency, improving the financing of fuel, machinery, and industrial inputs. Import-dependent sectors gain predictability as FX volatility declines. The narrowing current account deficit reflects this improved external balance. Yet Kenya’s export base remains narrow, dependent on horticulture, tourism, and a few service niches. Without growth in value-added manufacturing and agricultural processing, the external sector remains vulnerable. Stability is returning, but export diversification remains an urgent structural task.

Businesses

For businesses, macro stability reduces uncertainty and allows clearer planning for investment, procurement, and pricing decisions. Imported input costs are easier to manage with a firmer shilling and lower inflation pressures. However, high lending rates and conservative banking conditions restrict credit access. SMEs, in particular, struggle to secure financing for expansion, even as the environment becomes more predictable. Larger firms may adapt well, but smaller ones face tighter constraints. The challenge is creating stability that also supports growth for enterprise.

Investors

Investors now view Kenya as one of Africa’s strongest high-yield recovery stories, reflected in heavily oversubscribed Eurobond issuances. The combination of IMF oversight, stronger reserves, and early repayment discipline signals reliability. Falling bond yields confirm improving sentiment across the sovereign curve. Yet investors remain alert to political dynamics and revenue risks that could alter the fiscal outlook. Global risk-off episodes or policy slippage could still shift market perceptions quickly. Kenya is back in favour, but investors will monitor consistency closely.

What the future looks like

The future will depend on whether Kenya can transform its regained credibility into structural strength. The Treasury’s plan to reduce debt to 52.8% of GDP by FY 2027/28 is achievable only if revenue broadening, export expansion, and fiscal discipline persist. Without export diversification and productivity gains, the country risks re-entering the market in the 2030s under similar pressure. But if reforms hold, Kenya could shift from crisis management toward a sustainable, investment-driven growth path.

Conclusion

Kenya’s Eurobond comeback is one of the most impressive examples of fiscal recovery in a frontier economy. It shows how disciplined reforms, early repayment, strong communication, and IMF-aligned credibility can reverse even severe market scepticism. The data from 2020–2025, spanning deficits, debt levels, reserves, yields, and current account performance, reveals a clear upward trajectory that restored investor confidence.

But the comeback is not the final chapter. It is the beginning of a more demanding phase: structural reform, export expansion, and long-term fiscal discipline. Kenya has won back market trust, but whether it can convert that trust into durable economic transformation will determine the next decade of its development story.