What’s Driving the Naira and the Kwanza?

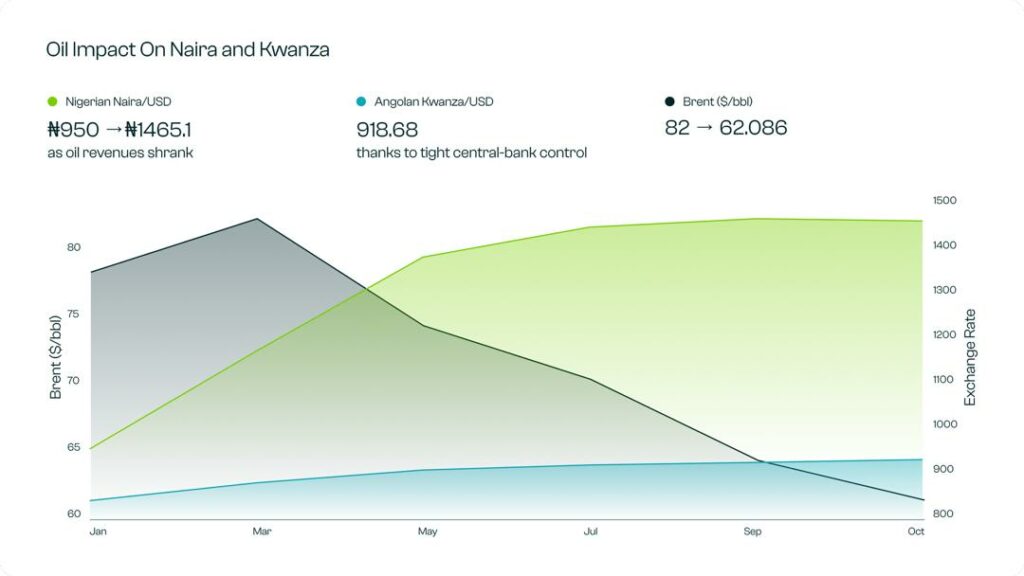

Oil markets are rebounding, marking the beginning of a new phase in global energy dynamics. The story of Oil Recovery and African Currency Resilience is unfolding across the continent. Economies like Nigeria and Angola are navigating the ripple effects of changing oil fortunes. Nigeria’s naira (₦) is showing signs of stability amid production gains and policy reforms. Angola’s kwanza (Kz), on the other hand, maintains steady ground through prudent monetary management.

Global Oil Outlook

Oil prices have improved slightly in 2025 but remain under pressure. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects global oil supply to rise to over 106 million barrels per day by 2026. This increase could create a surplus that keeps prices low. At the same time, OPEC+ countries, including Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Nigeria are gradually lifting their production cuts. These cuts amounted to about 2.2 million barrels per day and had been in place since 2023. This means more oil in the market, but not necessarily higher prices. Brent crude is currently trading around $62.5 per barrel, down from earlier highs in the year.

Nigeria: Recovering Production but Limited Price Gains

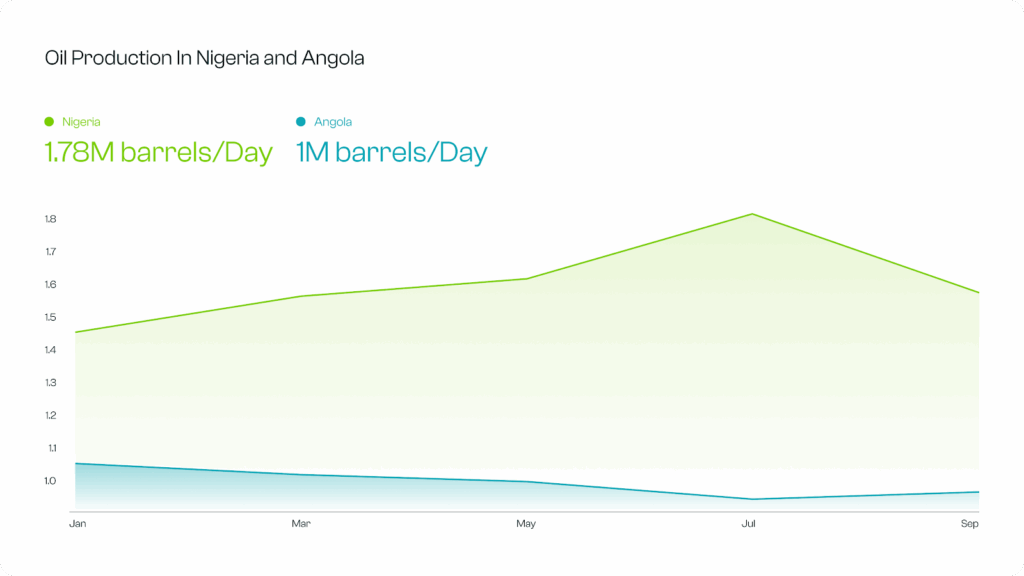

Nigeria’s oil production has finally started to improve. According to OPEC’s July 2025 report, the country produced around 1.78 million barrels per day, as shown in Figure 1. This output was slightly above its official quota. This recovery has helped increase foreign exchange inflows, giving the naira some stability. However, because oil prices have not risen much, Nigeria’s earnings from each barrel remain modest. Combined with high demand for U.S. dollars, the naira still trades around ₦1,465₦ per U.S. dollar. The government has introduced several reforms to improve transparency in the foreign exchange market. These measures have helped narrow the gap between the official and parallel market rates. Still, Nigeria’s currency stability depends more on consistent oil production and non-oil exports. Disciplined monetary policy also plays a bigger role than rising oil prices alone.

Outlook:

If Nigeria manages to sustain production above roughly 1.8 million barrels per day, the outlook could improve. With stronger non-oil inflows and reserves, the naira may hold its ground or even strengthen slightly. But if prices dip further and FX demand remains elevated, depreciation pressures will re-emerge.

Figure 1: OPEC, Monthly Oil Market Report, July 2025

Angola: Stable Currency, Weak Oil Output

Angola’s experience is quite different. The country left OPEC in late 2023. It now produces just under 1 million barrels per day, as shown in Figure 1. This marks one of its lowest production levels in recent years. Even though Angola is no longer bound by OPEC quotas, its oil fields are aging, and new investment has been slow. With Brent prices around $62, Angola’s oil revenue is under pressure. However, the National Bank of Angola (BNA) has kept the kwanza exchange rate stable at around Kz 918 per U.S. dollar. This has created a sense of stability but it’s mostly due to government control, not market strength. The country’s 2025 budget assumes an oil price of $70 per barrel. If prices fall further, government revenue could shrink. This would increase pressure on the kwanza.

Outlook:

If oil prices hold or modestly recover and domestic production stabilises, the kwanza may remain broadly stable. But a sharper oil-price fall or upstream shock could force a depreciation event rather than gradual drift.

Figure 2: OPEC, Monthly Oil Market Report, July 2025

Analysts Corner

The current oil landscape signals a period for discipline rather than speculation among investors. Nigeria’s modest production rebound offers short-term currency stability, but low global prices mean margins will remain thin, benefiting only low-cost, well-hedged producers. Meanwhile, Angola’s steady kwanza highlights how policy-driven stability can conceal structural weaknesses, a reminder not to mistake temporary calm for lasting strength.

Oil investors are now urged to focus on efficiency, integrated plays, and companies with resilient balance sheets rather than chasing price-driven returns. Nigerians and Angolans, on the other hand, should view today’s stability as temporary, building savings in stronger currencies, managing imports wisely, and prioritizing financial resilience over consumption, as any dip in oil prices or policy shifts could quickly expose the fragility of the current calm.

The mixed oil recovery in Nigeria and Angola serves as a quiet reminder that global energy stability remains fragile. As OPEC+ unwinds its cuts and African output edges higher, more barrels are returning to the market, but without a strong demand surge, the increase only adds to downward pressure on prices.

For import-dependent economies, that’s good news: softer oil prices help ease inflation and energy costs. But for global investors, it also signals a slower earnings cycle for energy companies and weaker fiscal positions in key African suppliers, which could ripple through debt and trade markets.

In essence, while the world enjoys cheaper oil in the short term, the longer-term risk is underinvestment if producers can’t reinvest at low margins, future supply shocks may come faster and hit harder.